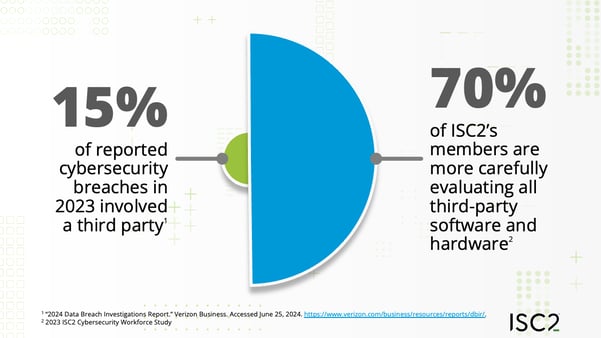

As organizations in every sector become more connected, and more digital, supply chains are extending and their cybersecurity is becoming more important: In 2023 15% of reported cybersecurity breaches involved a third party, according to Verizon’s 2024 Data Breach Investigation Report. The variety, scale and impact of cyber threats to supply chains is leading organizations to scrutinize not only physical or technical access, but also software and hardware dependencies. In a recent survey, 70% of ISC2’s members say they are more carefully evaluating all third-party software and hardware, including open-source software.

ISC2 convened an international volunteer task force to examine cybersecurity supply chain challenges. A key theme was the challenge around information sharing and how to increase the benefit to wider communities, notably small to medium-sized organizations, which are acutely impacted by the shortage of skilled cybersecurity professionals. The working group adopted NIST’s definition of cyber supply chain risk management (C-SRM), as “the process of identifying, assessing, preventing and mitigating the risks associated with the interconnected nature of Information and Communications Technology product and service supply chains.” This covers the entire lifecycle of ICT, software and information assurance, encompassing traditional supply chain management and security practices.

The task force noted that while there are a variety of resources describing emerging or good practices in supply chain risk management, approaches still vary. There is a lack of established guidance for supply chain risk management with collaborative information sharing included. It’s perhaps self-evident that information sharing is a critical part of supply chain security, but what information should be shared, with whom and how? These fundamental questions expose some of the current limitations and indicate what more could be done.

The industry is accustomed to sharing threat and vulnerability information, typically between trusted entities, in private forums, with handling protocols, mimicking the dissemination of intelligence more broadly. There have been improvements, notably in the automation of threat information, integration into security operations, publication of threat advisories, and the dissemination of mitigation advice.

Yet current practices fall short of international ambitions to build cyber resilience throughout supply chains. In this article, ISC2 calls for a concerted effort from the security industry and enterprises to build resilience in partnership with suppliers, particularly small to medium-sized sized organizations and open source software projects.

Individuals, commercial and public organizations, policy makers, regulators and organizations like ISC2 all have a role in building cyber resilience among supply chains and enhancing information sharing for this purpose. This article reviews the challenges and suggests a path forward.

The Challenges To Information Sharing

The task force identified several issues which undermine both the quantity and quality of information sharing. It’s important to understand these so that we formulate practical ways to improve information sharing throughout supply chains.

Commercial, Regulatory and Legal Concerns

Just as with individuals, organizations, particularly businesses, can be reticent about sharing information. A business might feel revealing a breach or potential vulnerability will damage its reputation or its bottom line. Or both.

Organizations might argue that sharing any level of information about their security posture could provide cyber criminals with intelligence that could be exploited in a future attack. Smaller suppliers may be especially concerned that transparency about possible or actual security shortcomings in their systems or products will scare off customers. They may also be more concerned about the potential costs or their ability to rectify any shortcomings identified. These concerns can apply when it comes to highlighting security issues at third parties, where the act of sharing information could threaten the relationship itself: If a partner discloses security concerns at Acme Corp, how might Acme Corp react?

Organizations face increased obligations as governments aim to build cyber resilience, not least within critical national infrastructure. Information sharing obligations, specifically on vulnerability and incident reporting, are now common. But how they are implemented can have unexpected consequences. Paradoxically, potential fines could inhibit reporting, obscuring the true picture of how vulnerable – or secure – our supply chains really are.

There will be an inevitable impact on the pace and extent of information sharing when it carries legal risk. Current good practice notes that informal or unmanaged information sharing increases legal risk, according to NIST. While cyber regulation is shifting towards a duty to report issues, precisely what must be reported remains ambiguous. It is still being tested through the legal system and being clarified by regulators. Organizations might decide to wait and see just how aggressively regulators enforce new rules before assessing their obligations, along with the potential impact of non-compliance.

Ultimately, these developments are likely to foster new international norms and common requirements. For example, companies based outside the EU, but trading within it, may be subject to the EU’s NIS2 directive, or the Digital Operations Resilience Act (DORA) - or indeed their partners may be - and they will cascade requirements down to their own suppliers. But currently information sharing is inhibited by the need to balance commercial, regulatory and legal liability risks.

Silos

Information sharing can be stymied at multiple levels. Silos operate within and between organizations, preventing the free flow of information to wider communities of interest.

There have been outstanding community efforts to boost information sharing across sectors. ISACs for example, give a trusted group of peers in a sector the opportunity to work together and share information. They also build bridges between sectors and geographies.

Yet ‘trusted' information sharing communities are inherently exclusive. They need to be alert to the danger of membership criteria that excludes suppliers, particularly smaller organizations, or organizations which are not wholly immersed in that sector and who could make useful or perhaps novel contributions to the community security posture.

Even when information sharing processes are in place across a sector, it’s not a given that all the relevant parties are involved. Suppliers that don’t qualify, perhaps because of their size or because they are not seen as sufficiently part of the sector, could be missing out on valuable information, leaving those most in need of support cut off. Moreover, a sense of exclusion might compound suppliers’ worries that being open about security concerns could compromise their commercial relationships and prospects across the industry.

Silos also tend to be inefficient. When different groups or sectors don’t share information, or manage their own inventories, there is a danger of duplicating effort and wasting resources that could be targeted at security improvements.

Timing

The modern world is volatile and fast moving. With cyberthreats moving at machine speed, time is of the essence. Yet much information sharing is reactive, in the wake of an incident or vulnerability disclosure. Despite significant improvements, notably publicly disseminated government advisories and enhanced mitigation advice, suppliers may only receive security correspondence after an issue arises. Yet they will be expected to react under time pressure, without the benefits of ongoing, proactive collaboration.

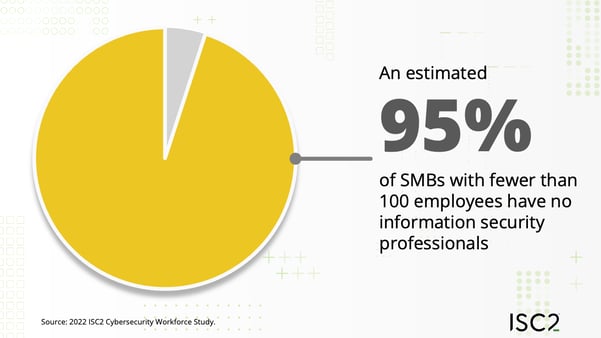

Workforce Shortage

The global shortage of skilled cybersecurity professionals is felt most acutely by small to medium businesses, who represent a significant proportion of supply chains and the overall economy. ISC2 estimates that up to 95% of small and medium-sized businesses with fewer than 100 employees have no information security professionals. When it comes to information sharing, the most excluded (perhaps least trusted) organizations are the ones with fewer security resources, which are ironically those most likely to benefit from information and assistance.

Human Nature

There is clearly a need for cyber professionals to connect, both formally and informally, ideally face to face, to build trust which can be critical in a crisis. But humans don’t stay in one place. Intra and inter company moves can spread or disrupt the chain of trust. Moreover, while they can be critical in a crisis, one-to-one relationships between professionals simply don’t scale.

Another aspect of human nature is to think that information is power and transparency is inherently exposing, thus can be perceived as weakness. Enforcement practices, more prevalent in regulated environments, can reduce psychological safety and inhibit information sharing. This leaves organizations reacting to an emergent situation, deprived of the opportunity to collaborate and prepare based on threat information. Writ large, collective resilience is undermined by individual behaviors.

Sometimes the Dam Does Burst

Despite all these hurdles, there are clearly times when cyber information is shared quickly, broadly and effectively across supply chains. Task force participants cited the Log4J crisis or the WannaCry attack as examples where “the dam burst”. Such events also highlight what can happen when political will is engaged. That in itself is a concern because political attention is limited.

Participants noted that it is possible to find examples of organizations reacting to a crisis by pulling up the drawbridge and choosing not to share information. It can all depend on precisely which sort of crisis we’re talking about.

Ways Forward

To build cyber resilience throughout supply chains, we must find ways to encourage organizations throughout the ecosystem to step beyond sharing vulnerability and threat information, towards sharing information and resources that can drive security capability development. We also need to consider how information can be shared across and between networks, not just within networks.

A New Model for Information Sharing

Once we think through these challenges, a new model for information sharing starts to take shape, one that truly takes account of our increasingly connected economy. The task force identified the following principles for this new model.

Positive

This begins with rethinking how organizations and broader industry groups can reduce supply chain risk; by reorienting information sharing towards capability development. Central to this is how larger, “prime” organizations with well-resourced security teams co-exist with their smaller, less resourced, but still critical, smaller counterparts. This will require executive support and leaders to set the tone and help navigate the complex risks and ambiguity that currently inhibit information sharing.

Those with the greatest capabilities – governments, enterprises, security companies, and industry associations – should shoulder the obligation to proactively share information that builds security through their digital supply chains. This can be focused on topics that directly impact supply chain risk, for example vulnerability management, but extend to adjacent topics, such as identity (and privileged) access management for suppliers with logical access, or awareness of security resources more generally.

Inclusive

Enterprises will naturally focus on their own supply chains, regulators will focus on their industries and the most systemically important actors therein, while governments will focus primarily on the public sector. Managed service providers play a critical role in securing medium sized businesses. But all, together with voluntary organizations, should explore and create opportunities for security professionals to assist small and micro-organizations that are typically underserved by the security industry.

This includes considering how to make information sharing networks more inclusive of smaller players. It could also mean the creation of new supplier communities, meeting suppliers where they are, or fostering links connections within an organization's supplier base, to cross-pollinate and accelerate capability development. This would make it easier to share both information and best practice, for example around mitigation steps, or knowledge of security controls.

Proactive

Suppliers should be engaged with cybersecurity before vulnerabilities are identified, or incidents arise, ideally during contracting. Proactive engagement should start with setting expectations, creating the conditions that will stimulate bi-directional information sharing. If smaller organizations realize that being transparent makes them more viable as a partner, they will be more willing to share. At a minimum, collaboration activity should include vulnerability management processes, incident response planning and ideally exercising, as the fastest means to reduce the impact of cyber incidents that cannot be avoided.

Towards a Digital Commons

With resources limited and supply chains extending, the new model must embrace approaches that create a common view of a given organization’s security posture. It should reduce the duplication of effort across organizations and networks, removing silos and enabling more efficient allocation of security resources. This approach should leverage technology for scale and speed – moving towards real-time monitoring.

Given that commercial actors are the most likely develop innovative solutions, a true digital commons requires common standards for interoperability. Standards should cover not only information sharing protocols but also the baseline observable indicators from which security posture can be developed. Advances in software supply chain risk indicators - such as the software bill of materials, which accounts for the provenance and security of software components, and greater visibility of the connected supply chain network, including concentration risks around key ‘node’ suppliers - must be matched in other categories of cyber supply chain risk.

Improving visibility and transparency of security posture within supply chains should shift effort from identifying to managing risks, freeing up scarce resources to spend time on activities described above.

Conclusion

Suppliers underpin the global economy, the commercial success and operational achievements of our interconnected ecosystem. Clients stand on their shoulders.

Organizations interoperate technically, whether they like it or not, while responsibility for disrupting cybercrime and maintaining economic and commercial resilience in the context of globally disruptive events is inescapably shared by the entire ecosystem.

When incidents do inevitably happen, communication needs to be transparent and agile to support collaborative triage and treatment of whatever the situation presents.

To facilitate information exchange those of us in supply chains must address the obstacles to sharing information. This action involves creating a culture where the entire ecosystem encourages discussion and disclosure, reorients current practices towards activities that reduce cyber risk, along with leveraging technology to collaborate at a pace that matches the volatile world we operate in.

It also means all organizations, but especially the biggest and best resourced, being prepared to cede some of their power – and their information – to benefit the ecosystem as a whole.

This isn’t a pipedream. Mutual support is a cornerstone of critical areas of social, political and business life, and much of the technical infrastructure that supports our digital way of life.

ISC2 will look at how it influences practices within its community – helping smaller organizations understand the positive consequences of disclosure and encouraging larger organizations to mitigate the negative consequences of doing so.

References

- Verizon’s 2024 Data Breach Investigation Report

- Good Practices for Supply Chain Cybersecurity

- NCSC Supply Chain Security Guidance

- CISA ICT Supply Chain Resource Library

- NIST Management Practices for Systems and Organizations

- Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Releases Version 2 of the National Cybersecurity Strategy Implementation Plan

- The McPartland Review of Cyber Security and Economic Growth

- NCSC 10 Steps to Cyber Security

- The 18 CIS Critical Security Controls

- SEC Disclosure of Cybersecurity Incidents Determined to Be Material and Other Cybersecurity Incidents

- 2022 ISC2 Cybersecurity Workforce Study

Contributors

This paper forms part of the output of the international volunteer task force assembled by ISC2 to examine cybersecurity supply chain challenges. Participants came from a variety of regions and industries, leveraging their professional knowledge and experience to contribute individually as cybersecurity professionals.

Contributors to this report and the task force include:

- Steve Brown, Vice President, Cyber Security & Resilience – Mastercard

- Christopher Geiger, CISSP, Vice President, Internal Audit and Enterprise Risk – Lockheed Martin

- Steve Johnson, CISSP, Information Security Manager – Risk Ledger

- Hoo Chuan Wei, CISSP, Chief Information Security Officer – StarHub

- Riaan Naude, CISSP

- Grace Nwokobia, CISSP

Represented industries include cybersecurity, financial services, telecommunications, defense and engineering. Participants came predominantly from the U.S., U.K. and Singapore.

- Find Out More about ISC2's Supply Chain Security course, for developing a systematic approach to assessing and mitigating supply chain risks

- Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM) through Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC) will help you address the growing complexity of supply chain cybersecurity

- First Steps for Supply Chain Security looks at the importance of mapping your supply chain and tracking inventory